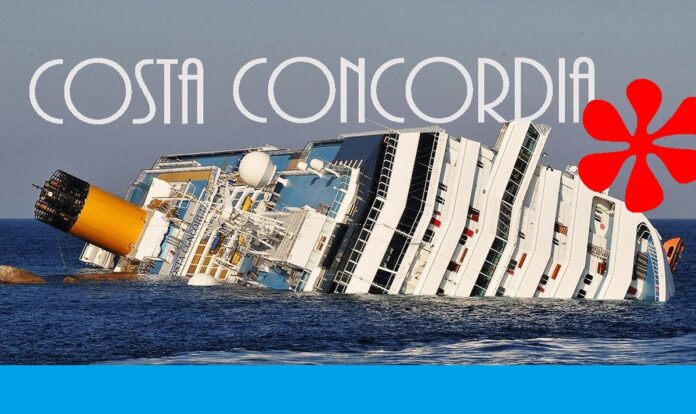

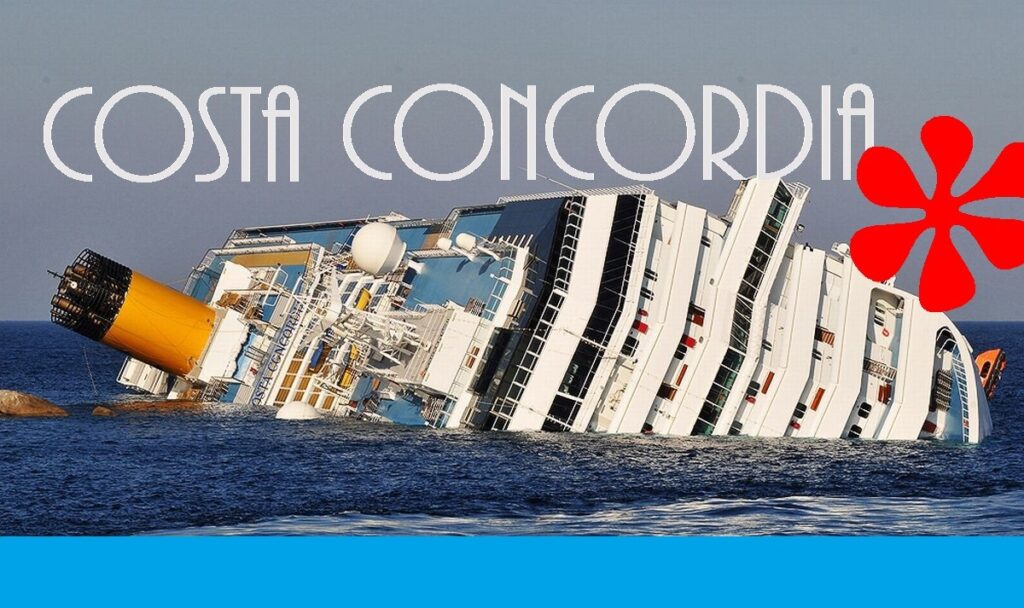

(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) On 13 January 2012 at 21:45, Costa Concordia struck a rock in the Tyrrhenian Sea just off the eastern shore of Isola del Giglio. This tore open a 50 m (160 ft) gash on the port side of her hull, which soon flooded parts of the engine room, cutting power from the engines and ship services. With water flooding in and the ship listing, she drifted back towards the island and grounded near shore, then rolled onto her starboard side, lying in an unsteady position on a rocky underwater ledge. The evacuation of Costa Concordia took over six hours and of the 3,229 passengers and 1,023 crew known to have been aboard, 32 died.

The graphics and maps below reveal more about what happened.

The Costa Concordia left the Italian port of Civitavecchia at 19:18 local time (18:18 GMT).

The ship was heading out on a week-long cruise around the Mediterranean with 3,206 passengers and 1,023 crew onboard.

As it made its way north-west along the Italian coastline, Captain Francesco Schettino ordered the ship to be steered close to the island of Giglio as a “salute”.

Italy’s Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport published a detailed timeline of events in its report into the accident(PDF), released in May 2013.

Other details emerged at pre-trial hearings, including excerpts of the frantic conversations between the Captain and his crew in the aftermath of the accident, captured by the ship’s “black box” voice recorder.

Nearing Giglio just after 21.30, the captain gave the helmsman coordinates, followed by the warning “otherwise we go on the rocks”.

Minutes later, at 21:45, the Costa Concordia hit a rocky outcrop while travelling at around 16 knots.

How the Costa Concordia capsized

The ship was holed on the left-hand side, started taking on water and began to tilt. Engine rooms were flooded and power was lost.

The crew struggled to assess the situation and relayed incomplete information to the Italian authorities.

At 21:52 the chief engineer and electrical officer tried and failed to start the ship’s emergency diesel generator.

Shortly afterwards, passengers were told that the ship was suffering a “blackout”, but that the situation was under control. The same information was given to the harbour master at Civitavecchia.

Costa Concordia crew member tells coastguard “we have a blackout”

Positioning data shows that the Costa Concordia turned and began to drift back towards the island’s port soon after 22:00 due to, investigators say, a combination of the wind and the rudder positioned to starboard (right).

As it drifted, the ship then began to list in the opposite direction, possibly caused by water in the damaged hull rushing to the far side during the turn.

At 22:12, the coastguard called the ship to say passengers were reporting problems to the local police, but the captain replied: “We have a blackout and we are checking the conditions on board.”

At 22:22 the captain gave orders to tell the coastguard that they had had a “failure” and needed help from tug boats. The radio operator did this and added that all the passengers had been given life jackets, none was injured and there was a gash in the left side of the ship.

At 22:33 the general emergency alarm was raised and passengers told to go to muster stations and await instructions.

By 22:48 the ship had settled on the rocky sea bed, tilted by more than 30 degrees. The captain finally gave the order to abandon ship at at 22:54.

Most passengers escaped in lifeboats, but evacuation efforts were hampered by the angle of the tilting ship. The coastguard launched boats and helicopters to carry stranded passengers to safety.

At 23:19 Captain Schettino abandoned the bridge, leaving the second master to co-ordinate the evacuation.

However by 23:32 the second master also left the bridge. Around 300 passengers and some crew were still on board.

At midnight dozens of passengers remained, many clinging to the exposed side of the ship.

In a conversation recorded at 00:42, a coastguard commander ordered the captain to get back on board. He did not, and went ashore.

The rescue continued over the weekend, with the ship’s safety officer, Marrico Giampietroni, being discovered and evacuated with a broken leg at 12:00 on Sunday. A South Korean couple were also rescued.

A recording was released in which the coastguard ordered Captain Schettino to ‘get back on board’. Capt Schettino was arrested and later went on trial, charged with multiple counts of manslaughter and abandoning ship. He admitted making a navigational error, and told investigators he had “ordered the turn too late” as the ship sailed close to the island.

The ship’s owners, Costa Cruises, said the captain had made an “unapproved, unauthorised” deviation in course, sailing too close to the island in order to show the ship to locals.

Crash investigationAutomatic tracking systems show the route of the Costa Concordia until it ran aground on 13 January. Data from 14 August 2011 show the ship followed a similar course close to the shoreline, according to Lloyd’s List Intelligence. On 6 January 2012, it passed through the same strait but sailed much further from the island. Divers searched the ship as it rested on the seabed in about 20m of water. The operation had to be suspended a number of times as the ship shifted position. The sea floor eventually drops to about 100m.

The Dutch salvage firm Smit brought a barge alongside the ship and divers installed external tanks to collect the diesel. More than 2,200 tonnes of fuel was eventually extracted, but the engineers were unable to remove all of it from some of the most inaccessible tanks. The decision to salvage the ship, rather than break it up, was taken in May 2012, four months after the disaster. The contract – awarded jointly to salvage companies Titan and Micoperi – was described as an unprecedented operation. The ship was eventually refloated in July 2014 and taken to Genoa, for the final scrapping operation.

The captain Francesco Schettino, who was dubbed Captain Coward for his actions, was sentenced to 16 years in jail for manslaughter last year. More than 4,000 passengers were evacuated from the stricken vessel – but the captain fled before everyone had made it safety.

Salvage and scrapping efforts are estimated to have cost roughly £1.2billion – making it the most expensive maritime wreck recovery in history.

Watch video: Costa Concordia, Before and After (credit: TheSeaLad)

the numbers quoted regarding left behind after the senior officers left the ship are incorrect. According to the shore rescue services who had taken over the rescue and who maintained a record of those they took off the ship, they state that they rescued approximately 1270 passengers and a small number of crew. Added to this were 80 persons towed ashore in the three liferafts that were launched, 100 persons swam ashore and were taken off the rocks and a small number were rescued by helicopter. The main problem was that the crew only launched 3 out of the 69 liferafts. As these were for crew evacuation, instead they took the passenger places in the lifeboats.