(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) Ships are increasingly using systems that rely on digitalization, integration, and automation, which call for cyber risk management on board. As technology continues to develop, the convergence of information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) onboard ships and their connection to the Internet creates an increased attack surface that needs to be addressed.

Challenges in Maritime Cybersecurity

While the IT world includes systems in offices, ports, and oil rigs, OT is used for a multitude of purposes such as controlling engines and associated systems, cargo management, navigational systems, administration, etc. Until recent years, these systems were commonly isolated from each other and from any external shore-based systems. However, the evolution of digital and communications technology has allowed the integration of these two worlds, IT and OT.

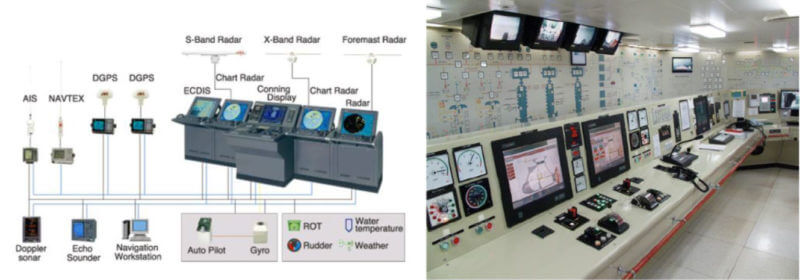

The maritime OT world includes systems like:

- Vessel Integrated Navigation System (VINS)

- Global Positioning System (GPS)

- Satellite Communications

- Automatic Identification System (AIS)

- Radar systems and electronic charts

While these technologies and systems provide significant efficiency gains for the maritime industry, they also present risks to critical systems and processes linked to the operation of systems integral to shipping. These risks may result from vulnerabilities arising from inadequate operation, integration, maintenance, and design of cyber-related systems as well as from intentional and unintentional cyber threats.

When addressing these cyberthreats, it is important to consider the uniqueness of OT systems, as these assets control the physical world. As such, there are certain challenges to consider, such as:

- OT systems are responsible for real-time performance, and response to any incidents is time-critical to ensure the high reliability and availability of the systems.

- Access to OT systems should be strictly controlled without disrupting the required human-machine interaction.

- Safety of these systems is paramount, and fault tolerance is essential. Even the slightest downtime may not be acceptable.

- OT systems present extended diversity with proprietary protocols and operating systems, often without embedded security capabilities.

- They have long lifecycles, and any updates or patches to these systems must be carefully designed and implemented (usually by the vendor) to avoid disrupting reliability and availability.

- The OT systems are designed to support the intended operational process and may not have enough memory and computing resources to support the addition of security capabilities.

Disruption of the operation of OT systems may impose significant risk to the safety of onboard personnel and cargo, cause damage to the marine environment, and impede the ship’s operation.

In addition to the ongoing integration of IT and OT, the future will bring MAS – Maritime Autonomous Systems. Based on artificial intelligence and Internet of Ships and Sea Services, the new generation of ships will be remotely controlled from the shore. MAS has a “disruptive” potential with implications in terms of technical, economic, environmental, legislative, and social impacts in the years to come. This development may also provide opportunities and new concepts that could improve logistics and, therefore, also improve the overall environmental impact of transport.

Maritime Cyber Threat Landscape

Completely digitalized shipping means greater reliance on digital, interconnected control and communication systems, says Isidoros Monogioudis, Adjunct Professor at the Hellenic American University.

Maritime digitalization is planned to increase performance, efficacy, and better collaboration within the industry. However, at the same time, it means a significant increase of the digital/cyber “attack” surface. Maritime industry, especially through vessels digitalization and with the numerous different Operational Technology devices deployed, creates a digital landscape previously unknown to a big extent due to the specific hardware and software being used. New security risks will be evolved with the impact being very significant mainly due to the direct connection with the physical world and the consequent operational damage.

A cyber incident in ships might have severe consequences for the crew, the passengers, and the cargo on board. Considering that many ships carry harmful substances, a cyber incident might have severe environmental consequences or might lead to hijacking the ship to steal the cargo.

The Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) has defined a cyber safety incident any incident that leads to “the loss of availability or integrity of safety-critical data and OT.”

Cyber safety incidents can be the result of:

- a cyber security incident, which affects the availability and integrity of OT (for example, corruption of chart data held in an Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS))

- a failure occurring during software maintenance and patching

- loss or manipulation of external sensor data that’s critical to the operation of a ship including but not limited to Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)

With more than 90% of the world’s trade being carried by shipping, according to the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization, the maritime industry is an attractive target for cyber attackers. The European Union has recognized the importance of the maritime sector to the European and global economy and has included shipping in the Network and Information Systems (NIS) Directive, which deals with the protection from cyber threats of national critical infrastructure.

Best Practices for Mitigating Maritime Cyber Threats

In 2017, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted resolution MSC.428(98) on Maritime Cyber Risk Management in Safety Management System (SMS). The Resolution stated that an approved SMS should consider cyber risk management and encourages administrations to ensure that cyber risks are appropriately addressed in safety management systems.

The same year, IMO developed guidelines that provide high-level recommendations on maritime cyber risk management to safeguard shipping from current and emerging cyber threats and vulnerabilities. As also highlighted in the IMO guidelines, effective cyber risk management should start at the senior management level. Senior management should embed a culture of cyber risk awareness into all levels and departments of an organization and ensure a holistic and flexible cyber risk management regime that is in continuous operation and constantly evaluated through effective feedback mechanisms.

In addition, BIMCO has developed the Guidelines on Cyber Security Onboard Ships, which are aligned with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework. The overall goal of these guidelines is the building of a strong operational resilience to cyber-attacks. To achieve this goal, maritime companies should follow these best practices:

- Identify the threat environment to understand external and internal cyber threats to the ship

- Identify vulnerabilities by developing complete and full inventories of onboard systems and understanding the consequences of cyber threats to these systems

- Assess risk exposure by determining the likelihood and impact of vulnerability exploitation by any external or internal actor

- Develop protection and detection measures to reduce the likelihood and the impact of potential exploitation of a vulnerability

- Establish prioritized contingency plans to mitigate any potential identified cyber risk

- Respond and recover from cyber incidents using the contingency plan to ensure operational continuity

“Maritime industry and its digital exposure have many similarities with industrial systems and the broader OT,” says Isidoros Monogioudis. “In this context, these companies must move very fast to the direction of protecting their systems, providing a reliable operating environment not only from a performance perspective but also from a security perspective. Both proactive and reactive measures must be developed and applied with the real-time security awareness and visibility being possibly the most critical solution since OT environment remains extremely sensitive in providing timely and accurate services.”

“Maintaining effective cybersecurity is not just an IT issue but is rather a fundamental operational imperative in the 21st-century maritime environment,” said the U.S. Coast Guard in their July 2019 security warning.

Source: Anastasios Arampatzis