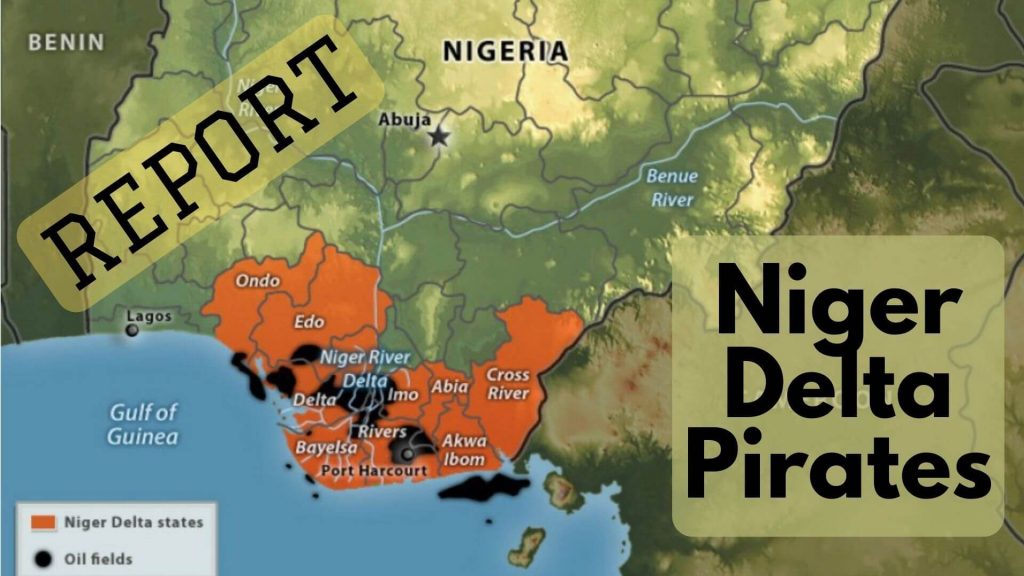

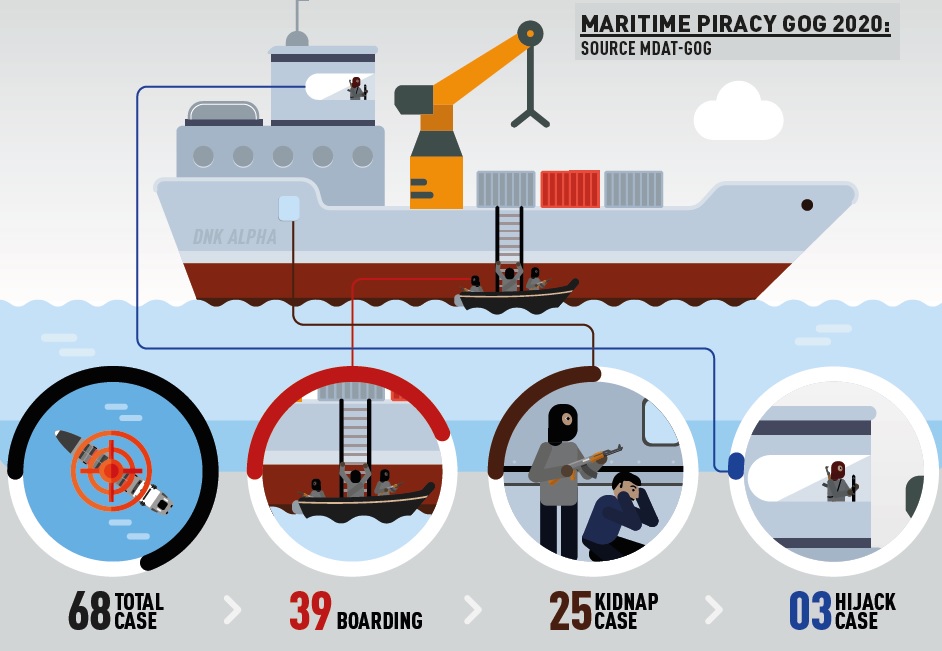

(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) The Gulf of Guinea region has a legacy of piracy, armed robbery and armed criminality. From politically motivated early militant groups, such as MEND, staging attacks against oil and gas infrastructure to modern-day criminal groups taking foreign crewmembers for ransom from international vessels transiting deep off the West African coast, piracy and maritime criminality has proven to be elusive to the many efforts to counter it. Indeed, for the past five years, the focus of piracy activities in the Gulf of Guinea has shifted from pirate groups targeting vessels to steal oil cargo (petro piracy) to current Kidnap for Ransom (K&R) piracy, with cases of up to 18 crewmembers kidnapped per incident.

Pirates of the Niger Delta delineates three types of pirate and maritime criminal groups, which operate in the region:

• Deep Offshore Pirates are capable of operating far from the coast of West Africa and target international shipping traffic. Deep Offshore pirate groups have become increasingly more sophisticated, as for example seen in their ability to take more hostages per attack. These groups have expanded their geographic reach further into the Gulf of Guinea, when incidents were previously concentrated in Nigerian waters. The number of Deep Offshore pirate groups is estimated to be between four and six.

• Coastal and Low-Reach Pirates operate up to 40nm from shore, primarily targeting local vessels. These groups usually operate close to their hideouts, or bases, onshore and have a limited operational range capacity. The targets are mainly fishing vessels operating along the coast, oil and gas support vessels and cargo vessels and tankers engaged in cabotage operations. Their modus operandi includes looting, racketeering and kidnapping for ransom, focused more on local crew than on foreign seafarers.

• Riverine Criminals are often referred to locally as ‘pirates’, though their criminal activity does not fall under the UNCLOS definition of piracy, as they operate in the waterways deep within the Niger Delta, where they target local passenger vessels, as well as engage in other crimes. Some arrests of ‘pirates’ reported by Nigerian agencies and media are highly likely of Riverine Criminals and illegal oil bunkerers, arrested in the creeks of the Niger Delta. These groups pose a more immediate security threat to local populations in the Niger Delta region than to international vessels and their crews.

Focusing on Deep Offshore pirate groups, the report also explores various roles within such Pirate Group Structure.

- Kingpins and Sponsors are responsible for organizing and providing the financial support to launch piracy attacks. Actors at this level may include high-level ex-militants who help to facilitate incidents of piracy for example by making funds available for initial investments (equipment, fuel, weapons, etc.). Actors at this level are likely also critical in providing protection and cover for the pirate groups.

- Group Leaders oversee initial attacks against vessels, including the kidnapping of seafarers. Generally, following a successful attack, a group leader will delegate control of hostage captivity to an onshore deputy. Group leaders will also oversee negotiations, though they do not often act as the negotiators, themselves.

- Negotiators, as the name implies, carry out negotiations for the release of hostages following a successful kidnapping operation. It seems that negotiators are often in high demand, likely fluctuating between and contracted by several different pirate groups for their knowledge about ‘ransom rates’ and negotiation strategies etc.

- Specialized Team Members possess a specific skillset to the attack team, such as navigation or engineering capabilities or the ability to hang grappling ladders on vessels being attacked.

- Attack Team General Members are members of teams who provide general support during an attack against a vessel. These members will yield weapons and may board the vessel to kidnap crewmembers when the others remain onboard the speedboat to keep watch and be ready to escape with short notice.

- Camp Guards and Onshore Support Roles are used following a successful kidnapping operation and manage operations at the hostage camps onshore in the Niger Delta. These roles guard captive hostages and provide general operational support for the camp.

Pirates spend their profits on an array of expenses. Following these pirate money streams illuminated that after a ransom is received a larger share goes to sponsors and/or kingpins, and smaller parts are paid to different categories of pirate group members. In addition to this sharing, a fraction of money may be reinvested into maintenance and purchase of equipment, such as speedboats and high-power engines, and weapons, such as AK47s. Beyond this, pirate salaries are spent on an array of expenses, largely dependent on the level the pirate group member occupies within the structure. Commonly, pirates spend money on family expenses, including school fees and healthcare. Pirates at higher levels may use their shares to purchase properties or vehicles. Group leaders may also share small amounts of money with the local community; one pirate group member interviewed noted about children aged 10 and older: “We give them some tokens because their parents are lacking too.” At lower levels in the structure, pirates may spend on substances like alcohol and drugs or on sex workers. Others note that they “don’t spend the money carelessly” but save in order to “buy land.”

Various enabling factors make combatting piracy difficult.

- Absence of convictions for the crime of piracy. While piracy has been known as a recurrent phenomenon in the Gulf of Guinea for several years, no conviction for piracy has ever been recorded in any country in the entire region. This is due in part to lack of adequate national legal frameworks – which have however developed over the past few years – and in part to a regional lack of capacity to intercept and arrest suspect pirates, collect evidence and prosecute the suspects.

- Alleged connections between pirates and high-level actors in powerful political positions are possibly established through secretive partnerships in illicit economies, like elected officials and candidates hiring pirate group members to assist with election protection, intimidation and violence – illicit ‘favors’ that may potentially, in turn, play a role in facilitating pirates evading justice. Further, the appearance of impunity for pirates may serve as a motivating factor for would-be pirates who see vast opportunity with little risk.

- The Gulf of Guinea region has a long history of socioeconomic underdevelopment – a fact in sharp contrast to the vast oil and gas wealth concentrated in the hands of foreign oil majors and regional political elites. This very juxtaposition was a major motivating factor for early militant groups operating in the region, including Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) and the Niger Delta Avengers (NDA); however, many socioeconomic conditions are largely unchanged despite claimed efforts to prioritize the development of coastal communities. Socioeconomic underdevelopment does not seem to be the primary incentive for contemporary K&R pirates operating in the region, but this is not to say that it does not contribute to motivating disenfranchised youths in the region who see few economic alternatives.

- Community support varies considerably for each type of pirate and maritime criminal groups. Interviews suggest that community support for Riverine Criminals is fading, which may be related to Riverine Criminals’ targeting of local vessels, including local passenger vessels, putting these groups in direct conflict with local communities. Meanwhile, Deep Offshore pirate groups occasionally share small tokens or percentages of their takeaway pay with communities facing widespread poverty and unemployment. It is unlikely that pirates donating to local communities have altruistic motives, however. It is more likely that community support is “bought.” Interviews suggest that for many coastal communities that ‘host’ pirate groups, this relationship is also characterized in important ways by an element of fear, including fear of reprisals if being seen to collaborate with security forces.

For more details, click below to download full report:

Source: UNODC

For more articles on maritime Piracy, click HERE