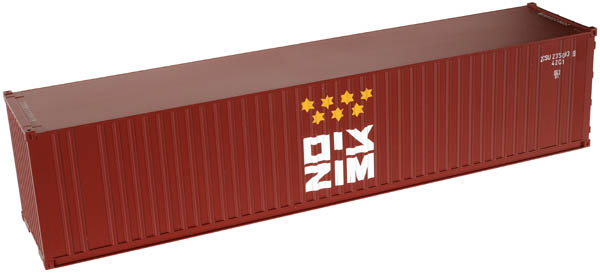

(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) Gliese Foundation has published twelve independent reviews of the largest container carriers. The table presents the ranking, name, score, number of pages of the Sustainability Report (still called CSR Report by some companies), the month of release of the report, number of years producing sustainability reports (the number available on the website, including 2019), and country in which each company is headquartered. Next, we present some of the highlights of each of the reviews.

Maersk:

Maersk:

Maersk's report tops the list; one can practically say that it belongs to a different dimension than all the others because it not only reports on its actions during 2019, but it also presents a vision for 2030 and 2050.

Maersk is the only liner that has gone to the level of detail of identifying twenty-five targets from twelve SDGs that the company is impacting.

The company states the two strategic targets on CO2 emissions: net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 and 60% relative reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030 compared to 2008 levels.

On GHG emissions, Maersk overpasses the IMO, leaving the London headquartered institution quite behind, as if the IMO's strategy were nothing else than a bureaucratic, outdated, and non-visionary document.

Maersk's technological sequence from 2020 to 2030 is particularly illustrative: During 2020-23, to explore the three working hypotheses for future fuels; 2023-27, to design vessel and supply chain pilots; and 2027-30, to produce the first ZEVs.

Regarding IMO 2020, Maersk has changed its environmental position on scrubbers due to profitability reasons. The expression "level of cleanliness of emissions" disappeared from the 2018 and 2019 reports.

The scrubbers' "elasticity" by Maersk is not an isolated case—Maersk has done it before. It did something similar with ships' demolitions, and it has been wavering about using the Arctic route.

Maersk's recent history seems to indicate that when profitability overcomes the environment, the company may backtrack (of course, that does not apply to the strong commitment on the decarbonization of its fleet for the year 2050).

Regarding ship demolition, one cannot condemn the company for having decided for Alang, but, of course, the "added cost of one to two million US dollars per recycled vessel" is clearly behind the decision.

Evergreen Marine:

Evergreen Marine:

Some Asian liners are doing quite well on environmental reporting: they have published Sustainability Reports for several years in a row, and, probably, trying not to fall too behind European companies, have done meticulous work with plenty of information and, above all, more data than their European counterparts.

Evergreen Marine and Maersk are the only two companies of all the twelve largest container carriers reporting on climate change adaptation beyond the most traditional reporting on climate change mitigation. That is because they are the only two liners committed to reporting as Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) requires.

Evergreen Marine deals with the transit along the Northern Sea Route without hesitating: not to sail the Arctic Circle. Evergreen Marine has taken a decision that neither COSCO, nor Yang Ming, ONE, HMM, or PIL, the other Asian liners have taken.

Evergreen Marine is among the leaders in supplier management. The company is not bluffing but going more in-depth than most of the other liners on its deals with suppliers.

Like all the other liners, Evergreen Marine tends to emphasize as its primary measure to reduce CO2 emissions the ordering of much more efficient newbuilds.

The company asks shipyards for its CSR before sending ships for demolition. If that is the case, one must congratulate Evergreen Marine, indeed. Regrettably, Evergreen Marine, as almost all liners, is silent about any final reflagging of those ships, and it does not say either if they are dismantled in real shipyards or beached in South Asia.

CMA CGM:

CMA CGM:

Most of the liners become entangled in something as easy as to define the main areas of concern of their environmental policy. That may be due to the preparation of the materiality matrix because there tend to appear five, six, or seven environmental issues. CMA CGM solves that issue effortlessly and straightforwardly.

Given that its primary short- and medium-term solution to reduce CO2 emissions is LNG, CMA CGM tries several times to present this fossil fuel almost as if it were a green fuel, which it is not at all. CMA CGM tries to offset its strong commitment to LNG with the inclusion of biofuels.

CMA CGM scores a great hit—as Evergreen Marine, MSC, and Hapag-Lloyd have also done—by its commitment of not using the Northern Sea Route.

CMA CGM does not limit itself to only mentioning energy efficiency actions (e.g., modification of bulbous bows, replacing propellers), but it also provides the numbers of vessels that have passed the "surgery" while at drydock.

CMA CGM and Maersk are the first only two liners that reported Scope 3 emissions during 2019. The results differ significantly: CMA CGM 16.5 and Maersk 34%. CMA CGM goes to great lengths to explain how it calculated those emissions.

Wan Hai:

Wan Hai:

Wan Hai could be small but, regarding environmental reporting, it plays in the major leagues. Its Sustainability Report is well organized and meticulously treated.

Contrary to Yang Ming, which was able to link the materiality matrix with the SDGs, Wan Hai follows a more traditional approach (as most liners do) by treating them as watertight compartments.

The Paris and Tokyo MoUs statistics deserve a subsection in each of the Sustainability Reports of each major liner, which only Wan Hai does.

Wan Hai venture into the realm of climate change adaptation despite it has not yet signed the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

Wan Hai goes into the supplier side as other liners, but without much success as most of them: the commitments are too general, not monitored, and not enforceable.

The representative of such a "small" company is the Co-Chair of the largest and most aggressive initiative currently in place to achieve the decarbonization of the shipping industry—the Getting to Zero Coalition.

Yang Ming:

Yang Ming:

Of all the Sustainability Reports of the largest liners in the world, the report by Yang Ming is the one that provides the most exhaustive set of data on CO2 emissions. If the shipping companies were to provide as much data as Yang Ming next year, we would conclude that the shipping industry has leapfrogged in its environmental reporting.

Yang Ming and the other companies tell us that they use a mix of "ingredients" (measures) that, in the end, reduces fuel consumption and CO2 emissions per TEU-km, but all of them say nothing about the contribution of each "ingredient" in the final result. In other words, we are left with a "dark box."

Yang Ming was able to join the materiality assessment with the SDGs and these with the specific environmental measures adopted by the company, all with great perfection like a skillful seamstress, while most of the other companies treat those topics as separate assignments.

ZIM:

ZIM:

One of the key challenges that liners have for the future is incorporating their suppliers into their Sustainability Reports—ZIM is not an exception.

Most liners retrofitted with scrubbers a share of their fleet (not the old ones) based on economic reasons; ZIM, on the contrary, followed the precautionary principle, which has become paramount when science has not concluded if some actions impact the environment, in other words, when the possibility remains open.

ZIM provides very comprehensive coverage of its utilization of digital technologies, which, among other benefits, has important environmental repercussions.

ZIM, as most liners, make claims about the second life onshore that many containers reach once it comes the time to replace them. But it donated barely ten containers during 2019. This shows why data matters.

One severe weakness of ZIM's report is the lack of GHG emissions reduction goals for the medium and long term—the company does not say anything beyond 2025. The report, however, does not include data about waste or other environmental indicators.

Hapag-Lloyd:

Hapag-Lloyd:

The report is quite "stingy" with numbers, believing that reporting is mainly text when it is not.

European companies are becoming complacent with their Sustainability Reports, may be convinced that they are the world leaders since Sustainability Reports have a European mark of origin. Some of the reports by Asian companies (not all, of course) have more data and are much more precise and to the point.

It is a weakness of Hapag-Lloyd and most other liners: besides reporting on CO2 emissions, the reports do not mention climate-change-related risks.

A fundamental weakness of the report is the scarcity of environmental data. All the relevant numbers one finds on the 14 pages of the environmental chapter for the year 2019 are... six! This is the key weakness we see in the report: no tables, no charts, no appendix with data. COSCO's report had more data, although it had only 35 pages and not 120 as of this one.

Something quite relevant was the signing by Hapag-Lloyd of the Ocean Conservancy's Voluntary Arctic Shipping Corporate Pledge to avoid the use of Arctic shipping routes.

Hapag-Lloyd is the only liner that can say the following: "We also entered into dialogue with Hamburg-based representatives of the Fridays for Future movement." All shipping companies boast about how they take care of the planet's future, but Hapag-Lloyd is the only one that has started a dialogue with the future climate change leaders of the planet. Amazing!

Another commendable action by Hapag-Lloyd, which is not usual among liners (or at least they do not report about it), is the way the company integrates and interacts with the City of Hamburg.

COSCO:

COSCO:

The Sustainability Report by COSCO could not be more different from the ones by MSC and Hapag-Lloyd (the two other companies we awarded 3.5 stars). The main differences between them are the following: COSCO's length is barely 35 pages, while MSC's is 138 pages and Hapag-Lloyd 122; COSCO includes environmental numbers in its report, MSC and Hapag-Lloyd very few.

COSCO's report has a characteristic that separates it from all the others we review. Its Sustainability Report talks mainly to the Communist Party of China (CPC). The document reports to the CPC that COSCO behaves according to Chinese policies and respects all the relevant national laws and regulations. That is why the report is so brief and to the point.

COSCO states that it complies with all the essential environmental laws in China, and, only at the very end, one international convention. COSCO presents its environmental measures not in the framework of the IMO's preliminary strategy (in reaction to the Paris Agreement), as all other companies do, but from the perspective of the Chinese government goals (the 13th Five-year Plan to Save Energy and Cut Emissions).

COSCO brings a recurring weather phenomenon--typhoons--into the picture to illustrate how the company is preparing itself.

MSC:

MSC:

The 138-page Sustainability Report by MSC has one feature that only Hapag-Lloyd's shares—there is almost no data, no numbers, no cold and objective numbers.

MSC ignored one of the most basic tenets of company reporting—to provide data, because, without data, one is left with narratives, stories, anecdotes. Even lesser-known and smaller companies such as Wan Hai are presenting much more environmental data.

However, the narrative in different parts of the report is laborious, engaging, story-telling.

Contrary to all the other liners that have done the materiality assessment, MSC does not reveal the matrix, only a vague figure. The matrix is important because it shows the company's priorities and its stakeholders to environmental and other sustainability issues.

The section about IMO 2020 was quite illustrative. Contrary to other liners that are relatively brief on this topic, MSC provides more information into the challenges that being compliant with the new regulation implied for its fleet.

The section about TiL is particularly useful. Liners tend to omit references to the terminals they own or make only some passing comments. MSC presents one of the best sections we have found about terminals, and with numbers.

In the chapter about short-sea shipping, inland shipping, and freight corridors, there is also interesting material since shifts from trucks reduce fuel consumption and positively impact the environment.

Nobody denies that decarbonization will not have only one solution, but the companies leading the effort, advancing faster than IMO, have priorities. MSC claims to have a 360-degree strategy to reduce GHG emissions. That is, let's be frank, the same as not having a strategy. In brief, the decarbonization ambitions of MSC could not differ more from the ambitions of the other giant, Maersk.

HMM:

HMM:

While all the other companies covered the period from January 1st to December 31st, 2019, HMM report's only covered from January 1st to June 30th, 2019! That cannot be: a year has twelve months, not six. Its 2019 report is barely half-2019 report.

It is a pity that HMM did not report for the entire 2019 because one can see from its report that it is one of the few shipping companies with the bold commitment to become carbon neutral for 2050.

Contrary to other companies that mention only a few of the improvements they are making to their vessels to reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, we found it relevant that HMM listed many of the measures.

We value that HMM has carried out a materiality assessment, joined green shipping initiatives, applied several environmental ISOs, endorsed the sustainable development goals (SDGs), and received different environmental awards. However, all of them are the new minimum in the container carrier industry in the 21st century.

ONE:

ONE:

We decided to upgrade by one star (to 2.5 stars) to Ocean Network Express (ONE) after it published its Sustainability Report in November 2020.

We are giving only 1.5 stars out of 5 to ONE: already in October 2020, it has not released a Sustainability Report for the operations from January 1st to December 31st of 2019. it is regrettable that a company like ONE, which transports between 6-7% of the world's total container cargo, has not released a sustainable report this year.

Given the lack of a Sustainability Report for the operations of the year 2019, we looked into two other sources of information: the environmental section on the website and the annual (financial) report for the year 2019. Regrettably, those sources were not useful either.

As with PIL, however, we do not want to end with a negative note. We value that ONE estimates the CO2 equivalent emissions for the period April to December 2018.

PIL:

PIL:

The last one of the top twelve largest container carriers is easy to select: Pacific International Lines (PIL). It receives only one out of five stars: PIL did not release a Sustainability Report for 2019, and it has never released any sustainability report. In other words, PIL stands out like a spot among its other eleven peers because it is the only one that is not reporting on environmental issues.

Not all those eleven companies have detailed and robust reports, indeed, but at least they have made an institutional effort to report on sustainability issues. We value such action strongly since the maritime industry, compared to other sectors, has arrived late to environmental reporting.

The problem is compounded because if PIL included some environmental data on its latest Annual Report, we could have taken the information from there. However, PIL has not published annual reports for the last years on its website, either.

PIL's lack of formal reporting is a pity because, on its website, there is some information about what the company is doing on the environmental front. All that is available are those paragraphs on its website, which, by the way, we do not know if they were published this year, one year ago, two years ago, or even earlier.

What comes next?

In the coming weeks, we will add some additional "chapters" to this review that it is almost becoming a short book. The most important will be the format of the ideal environmental reporting. Those readers that have gone through all the reviews may already guess the key sections that Gliese Foundation would be expecting for a Sustainability Report reach 5 stars out of 5 on environmental reporting. This chapter will present our ideal content and the key data that such an ideal document should include.

There will also be at least four chapters in which we will analyze some cross-sectional issues that tend to be included in almost all the reports. We are referring to the materiality assessment, in particular to the materiality matrix; the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); the CO2, NOx and SOx data; and from the appendixes, the GRI indicators.

The reasons we will discuss those issues are the following. First, there is a chaotic treatment of the materiality matrix among the liners. The issues and the relevance tend to be dispersed as if reports were coming from companies from different industries. Second, a very motley treatment of the SDGs also takes place. Some companies include all, others some of them and not necessarily the same. Once again, it gives the impression that they belong to different industries. Third, we will analyze the data submitted by the different companies about their emissions of CO2, NOx, and SOx. Up to now, we have limited ourselves to include a table in each review with the key data. In that chapter, we will put all that data together and have a full picture for more than 85% of the global liner industry, the percentage that represents those twelve companies. Fourth, we will present those indicators that should be added to the GRI's traditional reporting since the GRI reporting is not as complete as it should be for the shipping industry.

Source: Gliese Foundation