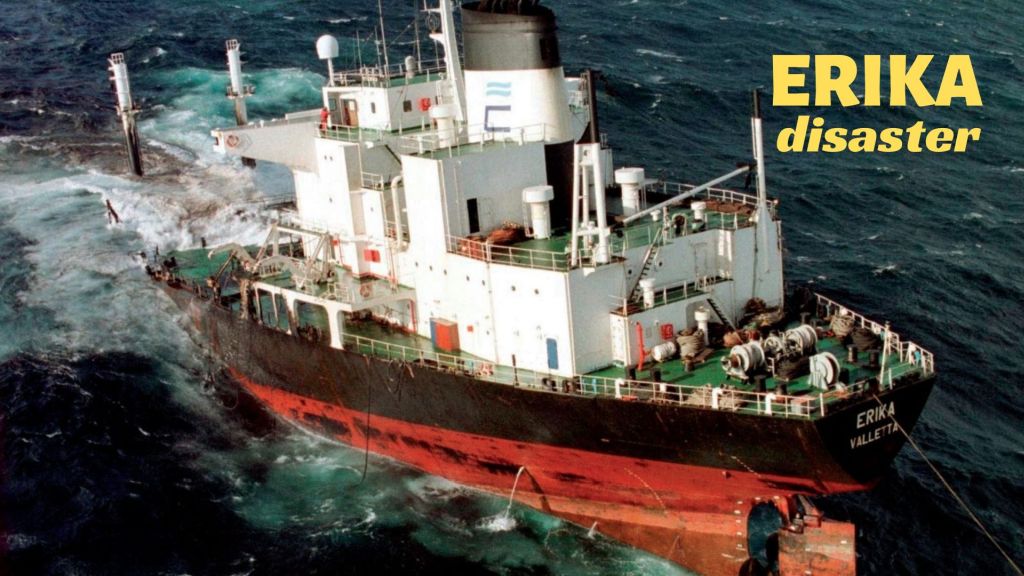

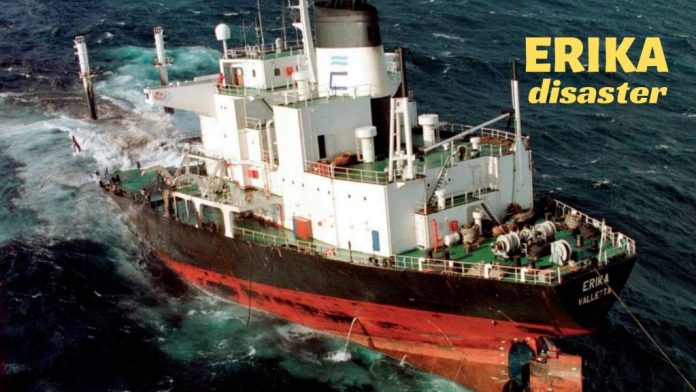

(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) On 12 December 1999, the Erika, a 25 year-old single-hull oil tanker, broke in two off France, polluting almost 400 km of French coastline and causing unprecedented damage to the marine environment, claiming the title of one of the most major environmental disasters of maritime history.

The incident:

On 11 December 1999, the Maltese tanker, Erika, laden with 31,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil (N°6), was en route from Dunkirk (France) to Livorno (Italy) when it was caught in very rough sea conditions (westerly wind, force 8 to 9, with 6 m swell). After sending out an alert message, then proceeding to transfer cargo from tank to tank, the captain informed the French authorities that the situation was under control and that he was heading to the port of Donges, at reduced speed.

On 12 December, at 6:05 am he sent out a Mayday: the ship was breaking in two. A rescue operation was immediately launched and the crew was winched to safety by French Navy helicopters, backed up by Royal Navy reinforcements, in extremely difficult conditions. The Erika split in two at 8:15 am (local time) in international waters, some thirty nautical miles south of Penmarc'h (Southern Brittany). The quantity of oil spilt at that time was estimated at between 7,000 and 10,000 tonnes.

The bow section sank the following night, a small distance from where the ship had broken up. The stern was taken in tow by the salvage tug Abeille Flandre on 12 December, at 2:15 pm, to prevent it from drifting towards the French island of Belle-Ile. It sank the following day at 2:50 pm. The two parts of the wreck ended up 10 km apart from each other, 120 m deep.

Pollution and response at sea

The Polmar Sea Plan was activated on 12 December at 6 pm by the Maritime Prefect for the Atlantic. The following day, the French Navy placed two deep sea support vessels equipped for pollution response on stand-by, to intervene as soon as the weather conditions would allow. They also opened discussions to mobilise the resources of Bonn Agreement Member States.

Initial aerial survey missions carried out by French Customs and Navy planes reported slicks drifting at sea, one of which was 15 km long and estimated at 3,000 tonnes. The slicks were moving eastwards at a speed of about 1.2 knots. On the following days, aerial observations identified a series of slicks made up of thick patches (5 to 8 cm thick) which tended to split up while continuing to drift parallel to the coast. On 16 December, small slicks of approximately 100 m in diameter gathered in a 25 km long and 5 km wide zone. As of 17 December, they showed a tendency to sink a few centimetres underneath the sea surface.

The Biscay Plan, a bi-lateral agreement for mutual assistance between France and Spain (signed on 7 December 1999), was activated on 19 December at 4 pm.

Pollution and response on the shoreline

The first incidences of the oil on the coast were noticed in Southern Finistère 11 days after the accident, on 23 December. Scattered landings continued the following days, hitting the islands of Groix and Belle-Ile on 25 December, and the Vendée region, north of the island of Noirmoutier, on 27 December. Owing to rough weather conditions (wind over 100 km/h, blowing perpendicular to the coast) and very high tide coefficients, the pollution was thrown up very high on the foreshore, reaching the top of cliffs exceeding 10 metres.

The Polmar Land Plans for the Vendée and Charente-Maritime departments were activated on 22 December. These departments were not hit by the pollution until 27 and 31 December respectively. The Polmar Land Plan for the Loire-Atlantique department was activated on 23 December, 3 days before the oil slicks reach the shore. The Polmar Land Plans for Finistère (hit on 23 December) and Morbihan (hit on 24 December) were activated on 24 December. In total, five departments activated their Polmar Land Plan.

On 26 December, 14 days after the sinking, the island of Groix, off Lorient, was severely affected and the bulk of the pollution reached the north and south banks of the Loire River. A viscous oil layer, 5 to 30 cm thick and several metres wide, covered parts of the shoreline.

The epilogue:

In 2008, Total, which chartered the rusting oil tanker, was fined 375,000 euros ($556,100) and told to pay 192 million Euros in damages to civil parties, including the French state.

Rina, the Italian maritime certification company that declared the Maltese-registered vessel seaworthy, and the ship’s owner and manager were also held responsible. Eleven others, including the ship’s captain, were found not guilty.

Total said it was considering an appeal and the firm’s lawyers said the ruling was out of kilter with international norms on shipping regulation.

But environmental groups like Greenpeace and plaintiffs welcomed a decision which punished an oil company directly for pollution caused by a ship it had chartered.

Read the Report of the enquiry into the sinking of the ERIKA below:

View more Maritime History, HERE.