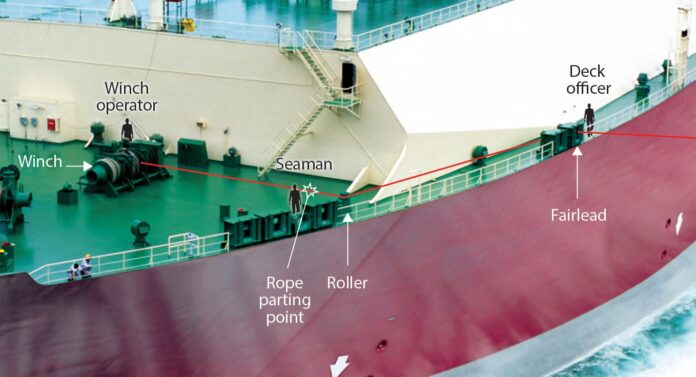

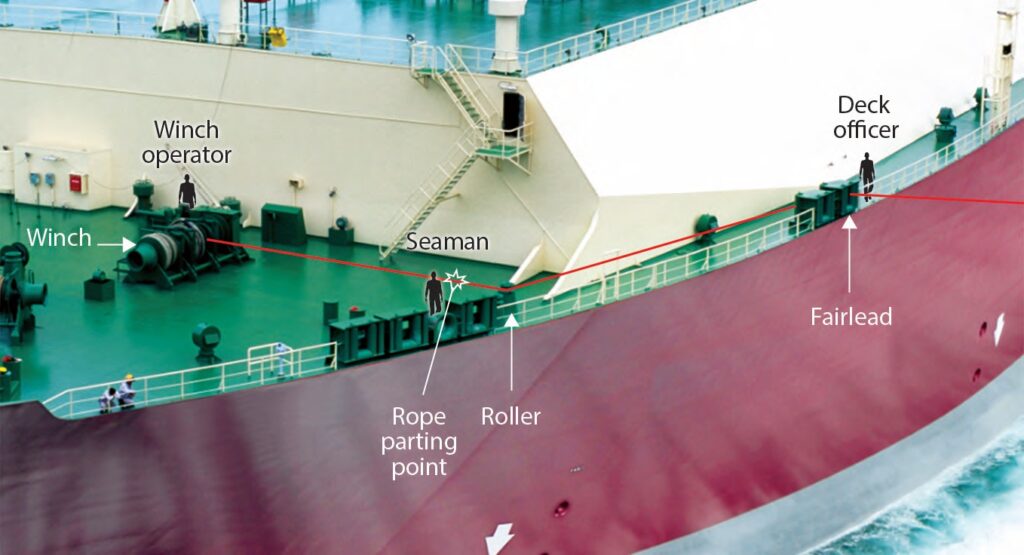

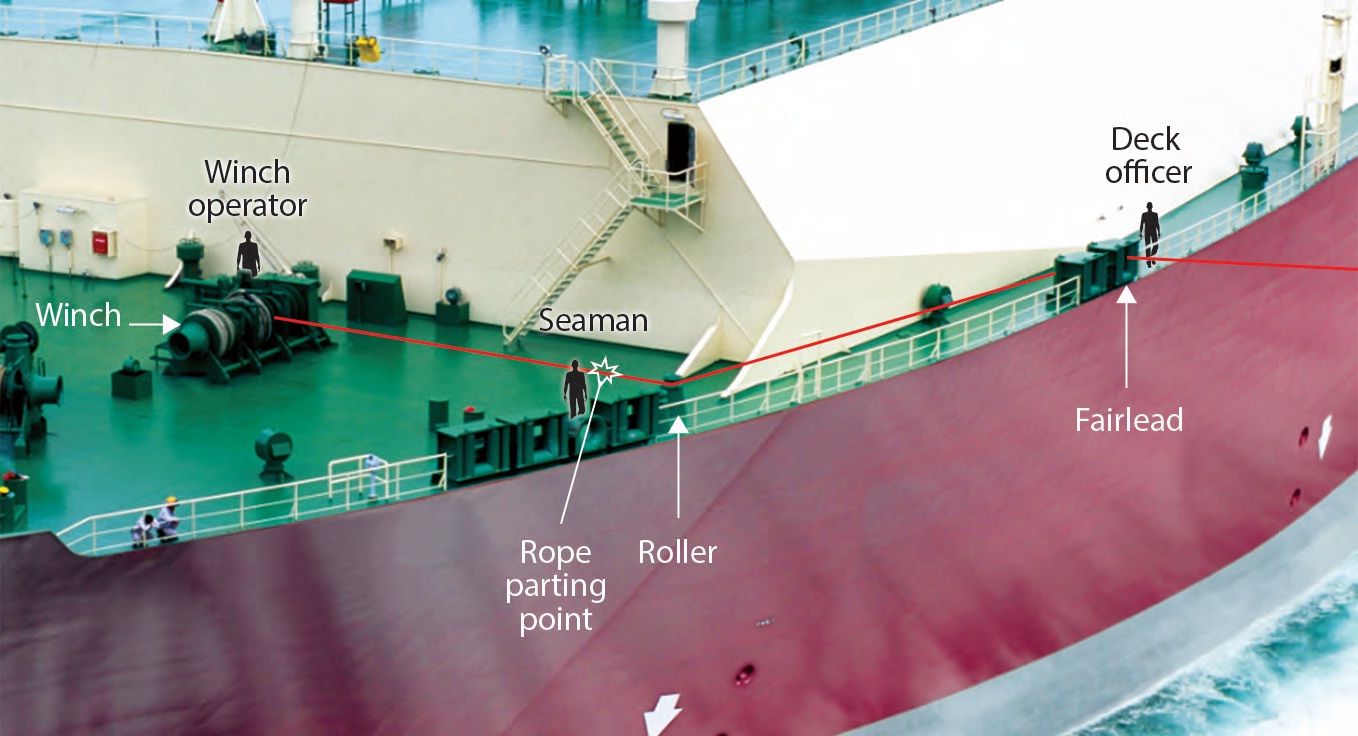

(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) A deck officer in charge of the forward mooring party on board a very large liquid natural gas (LNG) carrier was seriously injured when a tensioned mooring line parted. At the time of the incident, the deck officer was standing in a location that was not identified on board the vessel as being within a snap-back danger zone, resulting in a serious injury.

OCIMF has issued the below information paper which provides a brief description of the incident and considers if additional guidance, including that contained in OCIMF publications such as Mooring Equipment Guidelines (MEG3) and Effective Mooring, is required. Reference is also made to the incident investigation being conducted by the UK’s Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) and the recommendations contained in the interim Safety Bulletin issued in July 2015.

Source: OCIMF

The problem with snapback zones is that they are only a basic guide to what is perceived as the danger areas based on a general analysis of past accidents and mathmatical calculations. Once they are defined and painted on the decks, there is a tendancy of those working in the vicinity of the mooring lines to relax their guard if they are not in the defined areas. This is not what the zones are for. The whole area in the vicinity of mooring lines is potential dangerous when tension is put on the lines and we should be looking also at the whole seamanship aspect to avoid, if at all possible, putting extreme tension on one line and the training of those involved in mooring operations. However, what no one wants to talk about is the manning certification. Low manning is the major fault and the failure of most of the shipping companies to comply with the manning legislation and the Flag State enforcement is where the real blame should be placed. Painting lines on the mooring decks is no substitute for sufficient crew to properly tend and handle the lines.

What initiallly seemed like a good idea must now be reconsidered and even their removal considered to bring back the reaisation of the whole area is potentially dangerous.

Dear Capt.Lloyd,

Thanks for the input. It gives a good insight.

Best regards.

Reblogged this on Brittius.

Looking at the photo above, it is obvious that the winch operator(wo) has not a clear view on the mooring operation in progress, so he is just following the deck officer instructions. This means that the officer issues instruction to heave or to slack or to stay put, and there is a slight delay on the execution of the instruction. If in these moments the rope is in the beginning of an overtension, many are the chances that it will part. Then, you really cannot tell where the rope will swing, as the area of swinging is greatly related to the tendancy of twisting of the rope, which no one can tell, as it is different every time a rope is uncoiled.

Specially in the above photo, the rope has been led by two rollers, which added to the stresses and the friction.

Yes, the officer should be more cautious, but the real reason to my opinion, was why the rope was forced to take this much stress, by all the persons involved in a mooring operation, pilot, master, tugs, and then deck officer, wo etc...

Plans may exist, as a guidance, but the good seamanship is what will make a job safer and swifter.