(www.MaritimeCyprus.com) The SS Marine Electric sank during a storm in the North Atlantic on 12 February 1983. Of the 34 crew members on board, three survived, but only after enduring 90 minutes in extremely cold water.

The ship had passed all required inspections and surveys, but the subsequent USCG Marine Casualty Report revealed the inspections and surveys to have been perfunctory.

The storyline:

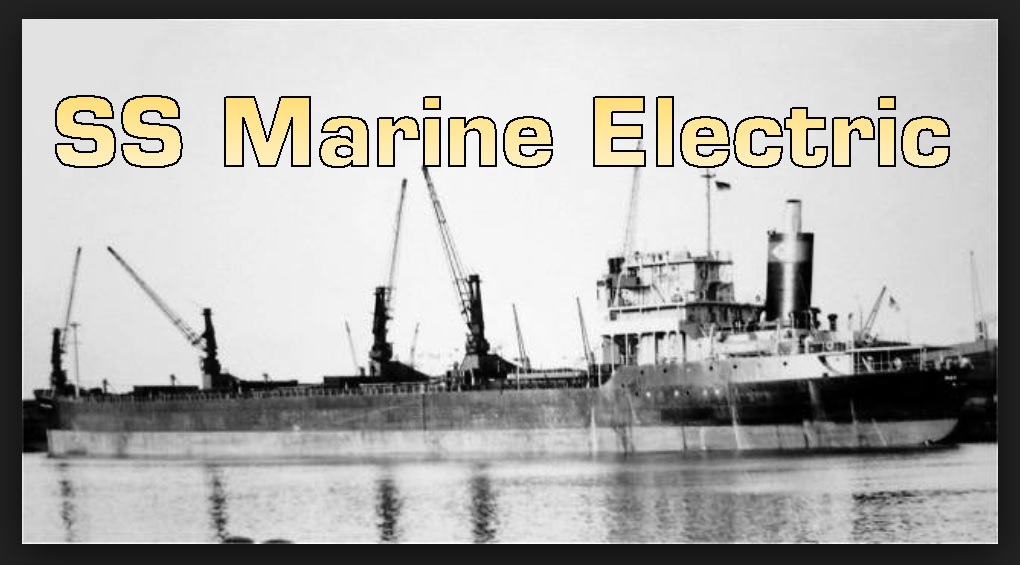

The MARINE ELECTRIC began its life as a T2 tanker, constructed for the United States Merchant Marine.

The MARINE ELECTRIC put to sea for her final voyage on February 10, sailing from Norfolk, Virginia to Somerset, Massachusetts with a cargo of 24,800 tons of granulated coal. The ship sailed in spite of a fierce (and ultimately record-breaking) storm that was gathering.

The MARINE ELECTRIC neared the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay at about 2:00 a.m. on Thursday, February 10. She battled 25-foot (7.6-m) waves and winds gusting to more than 55 miles per hour (89 km/h), fighting the storm to reach port with her cargo. The following day, she was contacted by the United States Coast Guard to turn back to assist a fishing vessel, the Theodora, that was taking on water. The Theodora eventually recovered and proceeded on its westerly course back to Virginia; the MARINE ELECTRIC turned north to resume its original route.

During the course of the investigation into the ship’s sinking, representatives of Mtl theorized that the ship ran aground during her maneuvering to help the Theodora, fatally damaging the hull. They contended that it was this grounding that caused the MARINE ELECTRIC to sink five hours later. But Coast Guard investigations, and independent examinations of the wreck, told a different story: the MARINE ELECTRIC left port fatally un-seaworthy, with gaping holes in its hull, deck plating and hatch covers. The hatch covers, in particular, posed a problem, since without them the cargo hold could fill with water in the storm and drag the ship under. And it was there that the investigation took a second, dramatic turn.

Investigators discovered that much of the paperwork supporting MTL´s declarations that the MARINE ELECTRIC was seaworthy was faked. Inspection records showed inspections of the hatch covers during periods where they´d in fact been removed from the ship for maintenance; inspections were recorded during periods of time when the ship wasn´t even in port. A representative of the hatch covers´ manufacturer warned Mtl in 1982 that their condition posed a threat to the ship’s seaworthiness. But inspectors never tested them. And yet, the MARINE ELECTRIC was repeatedly certified as seaworthy. Part of the problem was that the US Coast Guard delegated some of its inspection authority to the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS). The ABS is a private, non-profit agency that developed rules, standards and guidelines for ship hulls.

In the wake of the MARINE ELECTRIC tragedy, questions were raised about how successfully ABS was exercising the inspection authority delegated to it, as well as about whether the Coast Guard even had the authority to delegate that role. In the wake of the MARINE ELECTRIC investigation, the Coast Guard dramatically changed their inspection and oversight procedures.

The US Coast Guard report noted that ABS, in particular, "cannot be considered impartial", and described their failure to notice the critical problems with the ship as negligent. At the same time, the report noted that "the inexperience of the inspectors who went aboard the MARINE ELECTRIC, and their failure to recognize the safety hazards...raises doubt about the capabilities of the Coast Guard inspectors to enforce the laws and regulations in a satisfactory manner."

While the US Coast Guard commandant did not accept all of the recommendations of the Marine Board report, inspections tightened and more than 70 old World War II relics still functioning 40 years after the war were sent to scrap yards. As a result, inspection standards were drastically improved. The Coast Guard required that survival suits be required on all winter North Atlantic runs. Later, as a direct result of the casualties on the MARINE ELECTRIC, Congress pushed for and the Coast Guard eventually established the now famous Coast Guard Rescue Swimmer program. Though the safety of sailors at sea improved in the wake of the MARINE ELECTRIC tragedy, those improvements in safety came at the expense of 31 lives, condemned to a watery grave by poor maintenance and inadequate governmental oversight.

Watch the below documentary on the SS Marine Electric disaster:

For more Maritime History, click HERE